Women in American Civil Rights History

Women have been leading visionary struggles in American history since the nation’s founding.

In 1780, a formerly enslaved African woman named Mum Bett brought a case against the commonwealth of Massachusetts arguing for her right to freedom under a constitution that guaranteed all men to be free and equal. She won, and changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman. Her case was the death knell for slavery in Massachusetts.

From Abigail Adams to Harriet Tubman, Lucretia Mott to Angela Davis, women continue to drive history forward, refusing to allow the United States to deviate from a vision of equality.

Today, women remain at the vanguard of political organizing, heading movements such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. Civil rights — the rights that grant citizens equal protection and opportunity under the law — are constantly threatened. Women of different races, sexual orientations, and nationalities continue to stand together for America’s highest principles.

A Timeline of Civil Rights Movements and Important Women in American History

Many of the civil rights battles women find themselves fighting are overlapping and ongoing. Women have been structurally disenfranchised in multiple ways since the U.S. was founded. New frontiers and opportunities for immigration and westward expansion created new fronts for struggle. The vote was perhaps the most obvious of these, but not the most consequential.

At the same time as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and other middle-class white women were leading the suffrage movement, immigrant, Black, and Native American women like Lucy Parsons formed unions that fought for protections we enjoy to this day, such as the 40-hour workweek and eight-hour workday.

For African American women in history, civil rights have never been an either/or, only a both/and. Sojourner Truth was an abolitionist and suffragette. Rosa Parks was an anti-rape advocate and civil rights activist. Lucy Parsons was a labor organizer and birth control advocate. Without the groundbreaking work of Black women and other women of color, many of the rights and freedoms we claim as birthrights today would remain a dream.

We’ll begin our timeline of civil rights struggles with women’s suffrage, a movement that was a source of collaboration and conflict for many important women in American history.

Women’s Suffrage

Despite Abigail Adams’ famous exhortation to “remember the ladies,” the vital work women put in to support the Revolutionary War effort was not rewarded with equal representation when the time came to draft a constitution for the newborn United States of America. The roots of the women’s suffrage movement were formed at nearly the same time as the country.

White women experienced the injustice of being denied the vote keenly. Yet Black women were still subject to enslavement, and Native American women were victims of the ongoing genocide perpetrated against their people. Due to their greater privilege, upper- and middle-class white women were able to center the women’s suffrage movement around their interests. Still, Black women played a key role in the movement and worked with their white colleagues on other causes.

Many of the white women involved in the movement were also abolitionists. In fact, being banned from the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1840 because of their gender was what inspired Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton to hold the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. This crucial moment in women’s rights history led to later national conventions featuring speakers such as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.

Conflict Within the Suffrage Movement

A turning point in the suffrage movement — and indeed, the history of women in American politics — occurred during the debate over the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, a Reconstruction-era amendment that granted Black men the right to vote in 1870. Despite their ties to the abolitionist movement, many white suffragists were vehemently opposed to Black men being granted the right to vote over white women, with Susan B. Anthony famously declaring, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.”

With the conflict with their white compatriots brought painfully into the open, Black women’s rights activists eventually moved to form their own organizations. Mary Church Terrell was an educator and suffragist who, along with Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, formed the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. In 1913, Ida B. Wells, an activist and sociologist who was one of the founders of the NAACP, co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, a Black women’s suffrage organization.

The passage of the 19th Amendment granted women the vote in 1920. However, Black women and other women of color, along with working-class women of all races, continued to face obstacles to voting such as poll taxes and literacy tests. Particularly in the Jim Crow South, where de jure segregation (that is, segregation enforced by local laws) was still in effect, the dream of full suffrage had yet to be realized — which brings us to the civil rights movement.

Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was focused on eliminating legal segregation and discrimination against Black citizens of the U.S. Composed of ad hoc groups and organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the movement represented diverse interests and backgrounds while managing to coalesce around the goal of ending de jure segregation.

De Jure Segregation

Following the Civil War and the emancipation of enslaved Africans, former Confederate states passed the Black codes, a set of discriminatory rules that granted Black citizens some rights but denied them others. These rules were repealed with Reconstruction and the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

However, once Reconstruction ended and the Black political officeholders it ushered in were swept away, a succession of new and more discriminatory laws were enacted. They eventually became known as Jim Crow laws. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld these laws in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

Much of the activism around civil rights in the late 19th and early 20th century focused on preventing the murders of Black people at the hands of whites. During the Jim Crow era, lynching was used by whites who sought to terrorize Black citizens into meek acceptance of unequal treatment. In the early 20th century, NAACP co-founder Ida B. Wells-Barnett and charter member Mary Church Terrell were active in the organization’s anti-lynching campaigns, which laid a foundation for the movement work of the late 1940s to the early 1960s.

Peak of the Civil Rights Movement

Though the civil rights movement coalesced in the early 20th century, it did not begin to make major inroads at the federal level until the Supreme Court decided Smith v. Allwright in 1944, a Black voting rights case argued by Thurgood Marshall. Smith struck down the Texas Democratic Party’s race-based primary system and established the right of all citizens to freely participate in elections regardless of their race. Four years later, Shelley v. Kraemer struck down racially restrictive covenants in housing, and a decade later Brown v. Board of Education rendered Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” doctrine null and void. Still, equity for all remained a vision, not a reality.

In 1955, the nation’s attention focused on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama. Rosa Parks, a vitally important woman in American history, as well as a seasoned civil rights activist and member of the NAACP, made waves by refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a bus. The boycott her act inspired would last for a year, and lead to Parks and one of its organizers, Martin Luther King Jr., rising to national prominence. King would organize several more actions, such as the Birmingham campaign in 1963 and the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965.

As a result of the political pressures exerted by the civil rights movement and the more radical Black liberation movement composed of groups such as the Nation of Islam and the Black Panther Party, a few key pieces of legislation were passed: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Despite the many achievements of the civil rights movement, the rights gained under these laws continue to face challenges to this day.

Women in the Civil Rights Movement

Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, which was organized by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. His titular refrain became one of the best-known in history.

Less publicized were the remarks of Daisy Bates, a Black woman and civil rights organizer from Arkansas who spoke before King that day as a token to the hundreds of Black women leaders whose work in the movement was diminished due to the patriarchal attitudes of male organizers. Those same women leaders were asked to march on a separate street away from the main march.

As in other mixed-gender social justice movements, African American women making waves in history and the civil rights movement found themselves fighting with men for equal treatment at the same time they were fighting for equality in society.

American Indian Movement (AIM)

The American Indian Movement formed in 1968 to further the goals of Native Americans in the U.S. Focused on reclaiming tribal land sovereignty, enforcing treaty rights, and ensuring the equitable treatment of Native American citizens, the movement has roots in the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island’s (North America’s) historic opposition to settler colonialism.

A Brief History of Settler Colonialism and Native American Rights

Indigenous peoples existed on the landmass we know as North America for more than 20,000 years before Europeans arrived. These people were diverse, composed of multiple societies and cultures, with their own unique and sophisticated technologies.

Upon their arrival, Europeans began a genocide to claim the land as their own. Millions of Indigenous people lost their lives over the centuries to this campaign. Entire cultures were destroyed by the expansion of settler colonialism across the continent.

Indigenous peoples fought valiantly to maintain sovereignty over their sacred and ancestral lands, lands that were as much a living part of their communities as sisters and brothers, mothers and fathers. Yet in the end, the settlers’ aggression in their hunger for new territory was unmatched. The U.S. passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which led to the Trail of Tears relocations in 1838 in which the Cherokee people were forced to walk over a thousand miles to their new lands and thousands of people died.

With the passage of the Indian Appropriations Act in 1851, Indigenous people were rounded up and forced to live on reservations. The General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act, further diminished Indigenous rights by invalidating communal property ownership, a cornerstone of Native American cultures, and mandating that their tribal membership be replaced with U.S. citizenship.

Injustice and violence against Native Americans continued even after the reservation system was established. The U.S. government routinely violated its own treaties and Supreme Court decisions to make sure westward expansion and the mining of natural resources could continue. In 1890, the Wounded Knee massacre occurred as a result of U.S. military officials’ discomfort with the Lakota adopting a new form of spirituality. A Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, was shot along with hundreds of other tribe members.

In 1934, after the failures of the Allotment Act became clear, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act. The law was intended to increase tribal sovereignty and promote the revival of Native American cultures smothered by previous federal acts.

However, at the same time, the government was implementing policies that relocated Native Americans from reservations to urban areas to further their assimilation into white society. Government policies like these would eventually lead to the conditions that birthed the American Indian Movement.

By the time George Mitchell, Dennis Banks, and Clyde Bellecourt met with 200 other Indian activists in 1968 in Minneapolis, decades of alternating neglect and interference had taken their toll on the Native American community there. Urban conditions including police brutality were the touchstones they gathered around, but the movement later grew to encompass the issues it champions today, such as returning of native lands to original inhabitants and preserving Indigenous cultures.

AIM activists engaged in community patrols against police brutality, formed health services, and engaged in civil disobedience. One favorite tactic was occupation. The occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco took place over 18 months beginning in November 1969. Led by Ojibwe AIM activists, the occupation sought to secure the repurchase of the land for “twenty-four dollars in glass beads and red cloth,” a reference to the 60 guilders paid to the Algonquin for access to Manhattan Island.

A march on Washington in 1972 included a four-hour takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters, and an occupation of the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1973 — the location of the Wounded Knee massacre — would endure for 71 days.

In 1978, the Longest Walk march was held, an honoring of the relocations tribes were put through and an attempt to draw attention to multiple anti-Indigenous bills that were gathering support in Congress and among the public at the time. The bills were ultimately defeated.

Women in the American Indian Movement

Much like their sisters in the civil rights movement, Native American women throughout history and in the American Indian Movement had to contend with the patriarchal attitudes and behaviors of the men they worked alongside. Activist and author Mary Crow Dog, former wife of activist and political prisoner Leonard Peltier, spoke of the sexism she faced in her community in her book Lakota Woman.

AIM inspired younger Indigenous women such as Wilma Mankiller to assert their rights to equal leadership in their tribal communities. Mankiller, raised in San Francisco during the occupation of Alcatraz, became the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1985.

Asian American Movement

The Asian American movement centered on the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, the development of Asian American and Pacific Islander studies programs in universities, and securing reparations for Japanese families who were interned during World War II. The movement’s peak activity occurred during the 1960s and 1970s.

Members of the movement were radicalized by the war in Vietnam and the example set by the Black Power movement. Asian Americans began to contemplate their own long history of unequal treatment in the U.S. The forced relocation of Japanese citizens in 1942 was a still-fresh reminder of the many times the U.S. government bent its principles to accommodate anti-Asian discrimination.

Historic Discrimination Against Asian Americans

During the latter half of the 19th century, tens of thousands of Chinese Americans arrived on the U.S. West Coast seeking economic opportunity. A labor shortage threatened the construction of the transcontinental railroad, and Chinese workers filled the gaps, working long hours for less pay than their nonimmigrant colleagues. Some Chinese women were entrepreneurial themselves, translating their success at prostitution into madamhood.

Backlash from white Americans against Chinese immigrants led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law to significantly restrict immigration into the country. More laws restricting Asian immigration would follow, such as the Geary Act of 1892 and the Immigration Act of 1924.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1942, Japanese Americans were removed from their residences and forced into internment camps. Detainees lived under armed guard for years. When they emerged, they found their lives ruined and their assets and property seized by the government for back taxes — assets and property that in many cases could not be recovered.

Height of the Asian American Movement

During the Vietnam conflict in the 1960s and 1970s, anti-Viet Cong sentiment led to anti-Asian racism. This period cohered what had heretofore been a loosely affiliated group of primarily ethnic/national identities into a racial identity: Asian American.

In 1969 the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) was formed by activists at the University of California, Berkeley. The group united students of different Asian ethnic groups and nationalities. One of its later members, Richard Aoki, was first an early member of the Black Panther Party in Oakland. Along with Black and Indigenous activist groups, AAPA took part in the Third World Liberation Front strikes from November 1968 to March 1969, the longest student strikes in American history.

The Asian American movement succeeded in dispelling the popular conception of Asians as passive. As a result of their newly adopted racial identity, Asian Americans were also now able to mobilize as a political group.

Women in the Asian American Movement

The Asian American movement had many female leaders. One of the founders of the AAPA was a Chinese woman named Emma Gee. Grace Lee Boggs was a Chinese woman and activist in both the Black liberation movement and the Asian American movement who founded the Boggs Center. Patsy Chan, a Chinese woman with I Wor Kuen, a Marxist collective, helped organize the historic Third World strikes.

Important African American Women in History

Alongside the Black women mentioned in our movement timeline, many other African American women in history have struggled to bring this country closer to its ideals. Their work continues to resonate to this day. Here, we’ll look briefly at the lives of two of them.

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Height was a formidable civil rights activist and frequent counselor to politicians. In her youth, Height worked as a social worker in New York. She ran into Mary McLeod Bethune, who convinced her to begin working on anti-lynching and criminal justice activism with her at the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW).

The NCNW would elect Height the organization’s president in 1957. She led the NCNW to work with civil rights groups focused on voter registration in the South. Her work led her to the stage at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, but due to her gender she was not asked to speak.

Height went on to continue her civil rights work worldwide, securing a visiting professorship with the Black Women’s Federation of South Africa and the University of Delhi, India. In 2004, she was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and inducted into the Democracy Hall of Fame International. She died in 2010 at the age of 98.

Marsha P. Johnson

Black trans woman and activist Marsha P. Johnson was a key figure in the gay liberation movement, a civil rights movement focused on ending anti-LGBTQ discrimination and police brutality against the queer community. Johnson was on the front lines of the Stonewall uprising.

Johnson worked as a sex worker in her early years and at many other points in her life, which informed her politics and work with homeless transgender youth. In 1970, she formed STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) along with her friend Sylvia Rivera. STAR was a source of housing and social support for sex workers and homeless LGBTQ youth in New York. Johnson also worked with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) during the AIDS crisis.

Marsha P. Johnson died in 1992 under suspicion of foul play. Her life and its mysterious and tragic end are the subject of multiple documentaries.

Additional Resources

Biography, “Shirley Chisholm and the Nine Other First Black Women in Congress”

CNN, “Ten Incredible Black Women You Should Know About”

National Park Service, “Between Two Worlds: Black Women and the Fight for Voting Rights”

Important Native American Women in History

Native American women have long fought to bring this country to accountability. Let’s take a quick look at two of them.

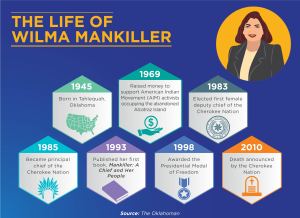

Wilma Mankiller

Wilma Mankiller was the first woman to be elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, a title she held from 1985 to 1995. Mankiller was born in Oklahoma but relocated to San Francisco as part of the U.S. government’s efforts to move Native citizens to big cities to facilitate assimilation. She became radicalized as a result of the devastation this move had on her family.

Mankiller was involved in supporting activists during the occupation of Alcatraz, and she worked in the Oakland public school system coordinating Indian programs while she took college classes. She created public works programs for the Cherokee Nation which led to her being elected deputy chief under principal chief Ross Swimmer, and then later principal chief herself.

Mankiller was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993, and she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998. She died in 2010 of pancreatic cancer.

Lyda Conley

Eliza “Lyda” Burton Conley was a Native American woman and activist who became the first woman admitted to the bar in Kansas. She was also the first Native American woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court.

Conley’s people, the Wyandot, were originally from Ontario, Canada, but were relocated to Ohio, and then to the territory of Kansas. However, when they arrived in Kansas, the land promised them was no longer available. A neighboring tribe, the Delaware, offered the Wyandot land. That land would become the Huron Indian Cemetery. The tribe later relocated again to Oklahoma after signing a series of treaties with the U.S. government in 1865 and 1867, the first granting them U.S. citizenship for land rights and the second allowing them to re-form as the Wyandotte tribe based in Oklahoma.

In 1899, the new tribal government made moves to sell the land in Kansas where the descendants of the Wyandot were buried, sparking outrage. Conley led a campaign against the sale of the Huron Indian Cemetery to the Kansas government and eventually took her people’s case to the Supreme Court in 1910.

Though she did not win due to lack of standing, Conley did not give up in her fight to protect the Huron Indian Cemetery. The cemetery was later declared a national monument, but Lyda Conley stood watch against anyone who would desecrate the graves of her ancestors until the day she died in 1946.

Additional Resources

Indian Country Today, “A Tribute to Those Who Always Imagined Native Women in the Congress”

Teen Vogue, “Five Native Women Leaders Who Made History”

Pow Wows, “Nine Famous Native American Women in History That You Need to Know”

Important Asian American Women in History

Aside from the influential women mentioned in our summary of movements, many other Asian American women in history have driven progress forward for the U.S. We’ll examine two here.

Patsy Mink

Patsy Mink was a Japanese American woman from Hawaii who became the first Asian American woman to serve in Congress and the first woman of color elected to the House of Representatives. She was also the first Japanese American woman to practice law in Hawaii.

Mink was born in Hawaii in 1927. She graduated from the University of Hawaii in 1948 with degrees in zoology and chemistry. After her applications to medical school were rejected, she decided to attend and was accepted to the University of Chicago Law School, from which she graduated in 1951.

By 1954, she had moved back to Hawaii and was admitted to the state bar. Hawaii became a state five years later, and Mink began her first unsuccessful campaign to serve in elected office. She was elected to the state Senate in 1962, and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1964.

Mink served in the House from 1965 to 1977 and undertook a brief run for president in 1972. During this time, Mink was one of the architects of the Title IX civil rights legislation. She also served as assistant secretary of state and worked in the private sector before returning to Congress in 1990, where she remained until her death in 2002.

Yuri Kochiyama

Yuri Kochiyama was a Japanese American woman, civil rights activist, and author who worked in the Black Power and Asian American movements.

Kochiyama was born in 1921 in Southern California. Her family was subjected to forced relocation during the Japanese internment of World War II. During this time, she had her first experiences with activism, writing letters to nisei soldiers in the U.S. military.

In 1946, Kochiyama married one of the soldiers who had been buoyed by her activist work and moved to New York City. There, in Harlem, she met Malcolm X and began working with Black liberation activists. When the Asian American movement emerged in the 1960s, Kochiyama’s intensity and experience catapulted her into leadership.

Kochiyama’s memoir about her experiences, Passing It On, received the Gustavus Myers Outstanding Book Award for 2004. Kochiyama died in 2014 at the age of 93.

Additional Resources

National Women’s History Museum, “Celebrating Asian American Women”

Teen Vogue, “4 Asian-American Women Who Changed History”

The Ongoing History of Women in American Politics

In 2020, the U.S. finds itself in the middle of a massive uprising. The Black Lives Matter movement seeks to redeem the vision laid out by our founding fathers — a nation where all people are equal. Women are at the forefront of this movement as well. Black Lives Matter was formed by three Black women in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s murder.

Women are also working within the system to try and achieve incremental gains. In 2016 and 2018, a wave of progressive women swept into Congress. One of these women, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, co-sponsored a bill known as the Green New Deal that rivals the original New Deal in its scope and impact. Another, Pramila Jayapal, is the first South Asian woman to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Like their foremothers in civil rights movements throughout history, women working in politics and activism today continue to deal with sexism and patriarchal oppression both in their own communities and in the larger society. These obstacles are a reminder for today’s women of promises that have yet to be kept, and a cudgel spurring them forward toward a future where oppression based on gender has been eliminated.

The history of women in American politics continues to be made.

Infographic Sources

History, Civil Rights Movement Timeline

National Women’s History Museum, Woman Suffrage Timeline

The Oklahoman, Wilma Mankiller: A Timeline

Thought Co., “History of the Asian American Civil Rights Movement”